TL;DR: I had a pretty good experience at Parexel and got money that covered my lacking student finance. I discovered the world of clinical trials and what to anticipate as a volunteer. They are a lot safer now than 10 years ago.

Last month, I completed 8 weeks of a clinical study without any health changes after being injected with a single dose of a study drug. This is the first brief I got before being screened:

The study drug being developed in this study is a compound called benralizumab for the treatment of asthma. This is [not] a first time into man study. This study consists of 1 night in-house and 9 outpatients visits. We are looking for healthy male volunteers (aged 18–55). Volunteers must be non-smokers for at least 3 months prior to screening. The inconvenience allowance for this study is £1,700.

But before we get started, let me take you back to how I got into clinical trials.

- Missed opportunity

- Study details

- Screening

- In-house stay

- Restrictions

- Outpatient visits

- What I discovered

- Conclusion

Missed opportunity

In the Spring of 2016, I saw an advert on a train in the Tube for Quintiles who were looking for paid volunteers for some studies. I was interested and so I went online to register to be screened for a trial for M923. The study drug, M923, has the potential to treat autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis. The trial would involve 2 nights stay and 13 outpatient visits before getting £2,910!

Some time later, I was invited for a screening and accepted to the trial subject to my General Practice (GP) sending my medical summary to Quintiles in time. This didn’t happen. I had a good healthcare experience from my GP surgery at that time, Farnham Road Practice in Slough, but they have been poorly let down by very slow admin processing.

Fast-forward past this missed opportunity, I had a look at some other drug research units and subscribed to Parexel’s email and SMS notifications. The table below is a 7-month summary of trials available before I chose one.

| Nights | Outpatients | Compensation (£) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1 | 906 |

| 3 | 2 | 1,080 |

| 5 | 13 | 3,840 |

| 20 | 1 | 2,750 |

| 8 | 2 | 2,128 |

| 7 | 1 | 1,489 |

| 6 | 9 | 2,150 |

| 6 | 8 | 2,350 |

| 3 | 1 | 1,050 |

| 5 | 6 | 2,029 |

| 5×3 | 1 | 2,750 |

| 1 | 9 | 1,700 |

| 19 | 4 | 3,575 |

Study details

The trial I was part of is study 230172 run by Parexel and sponsored by AstraZeneca, the drug developer (1)(2). I was given a 19-page document with participant information and a consent document. Up to 180 participants will take part in this study. The study is also being run at another study centre in Germany.

Simplified Study Title:

A Study in Healthy Volunteers to Compare the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion of Benralizumab when Administered using 2 Different Devices

Full Study Title:

A Multicenter, Randomized, Open-Label Parallel Group Phase 1 Pharmacokinetic Comparability Study of Benralizumab Administered using Accessorized Pre-Filled Syringe (APFS) or Autoinjector (AI) in Healthy volunteers

The main purpose of the study is to compare how much of the drug is taken up, its distribution, how the drug is broken down and removed from the body when administered through the 2 different devices mentioned above. Another purpose is to see how safe it is, how well it is tolerated and if it causes an immune response (anti-drug antibodies).

My participation in the study took 2 months from the overnight stay to the last outpatient visit, with my screening being the week before the start. Volunteers are free to leave the study at any time and without any reason. If you leave early you’re partially compensated by the fraction of the time you’ve taken part, and not by the number of outpatients you’ve been to for example.

Safety

The efficacy and safety of benralizumab have been shown in two large clinical trials in patients that suffer from asthma.

That’s what was mentioned in the information document and is supported by other sources. More than 2,000 patients received benralizumab and it was shown that the drug reduces asthma exacerbations (worsening) by up to 51% in two studies. I’m now realising the original first brief was wrong or at least ambiguous in saying this is a first time into man study.

Screening

Before getting screened, there are some requirements I had to meet before going in:

- fast from food & drink (except water) for the 8 hours before

- no alcohol 72 hours before

- no foods with poppy seeds 72 hours before and throughout the trial

- not taken part in a study in the 3 months prior

- no history of drinking more than 21 units of alcohol per week in the 12 weeks prior

- not donated one or more units nor had any other significant loss of blood in the 3 months prior

- not donated blood plasma in the 1 month prior

Fasting for 8 hours is not unreasonable, even more so considering screening and outpatients are usually in the mornings.

The screening took about 2 hours and it was their way of assessing me for the requirements of the trial. I was in a small group with other volunteers screening when a study doctor talked to us in more detail. We then signed the consent form after getting the chance to ask questions. I answered a questionnaire (smoking habits, alcohol consumption and such) before going through some physical assessments and sample collections:

- Physical examination, including height and weight for calculating Body Mass Index

- Urine sample

- Electrocardiogram (ECG)

- Blood pressure

- Blood samples (~97 mL)

To put 97 mL of blood into perspective, 470 mL is given in a single donation at the Blood Transfusion Service. The amount of blood collected varies but doesn’t exceed 470 mL. For this cohort of the study, my weight had to strictly be in the range 55.0–69.9 kg.

I got dates for my overnight stay and outpatient visits during my screening and were part of the agreement to sign. After my successful screening, Parexel sent a request to my GP for my medical history. I had to pay my GP surgery for this to be sent but Parexel reimbursed me.

In-house stay

There is some restriction on what can be brought in before going in, mostly to stop external food and drink. Inside we got set meals which were really good; I have no complaints. Weirdly enough, everyone gets vegetarian meals on their first day. The first day and night of standardised meals prepared us to a baseline state, so to speak, before dosing.

My cohort was the first for the study, at least in the UK. There were 5 of us and in the same ward. I was the youngest, at 21, with one man in his 40s and the rest in their 30s. The oldest man told me that he has been doing one trial per year for about a decade!

There were some brief medical tests and blood and urine samples before getting independent time to do anything. The lounge room had a relaxed atmosphere with books and newspapers to read, video games to play, TV and DVDs to watch, and a pool table and board games to play. There’s even laundry service for longer studies. I was able to do my studies on my laptop comfortably. There was also decent WiFi for browsing although I ended up using my phone’s hotspot to watch Netflix in HD during dinner.

I noticed there are definitely more men than women in the centre. The women there were mostly past child-bearing age, except for one woman who must have been in her 20s. Apart from pregnancy, a reason why women are less preferred to men is because of having more hormonal changes which can skew results.

Some were there for a trial involving heart-related medication and two were about to start a trial that restricted them from driving. That night I heard that a man got ill and was so bedridden that his food had to be brought to his bed. The nurses did take care of him but the study doctor hadn’t been reached.

In the morning, one person from my cohort would be sent home as they are a reserve until the rest get dosed. 1 in 5 people end up being a reserve and the choice is usually based on medical test results. This reserve can go straight to be screened for another trial or the same trial but for another day. The reserve is paid £225 for their time.

The study drug was injected with a random choice between the two devices and also randomly chosen into either left or right, of either the upper arm, abdomen or thigh. I got left upper arm and didn’t feel much of a sting at all and neither did the others; blood sample injections had way more of a sting.

We were given yellow cards to have on us at all times to present to any medical staff or use one of the phone numbers to reach the study doctor. I was injected at 8:44 am and was told to try to be at the outpatient visits for checkup at the same time, probably for scheduling purposes to avoid long queues.

Restrictions

Any restrictions I list here should only be taken as examples since generally they’ll vary between different trials and different research units but most may be similar. My restrictions during the trial, mostly until the last visit:

- no medication from 14 days before admission until the last visit, unless regular and prescribed

- only Paracetamol for the relief of pain and fever and after the Study Doctor’s approval

- no more than 2 units of alcohol per day

- no more than 3 cups of caffeine per day (1 cup = 250 mL of soda, 180 mL of coffee or 240 mL of tea)

- no high-energy drinks, such as Red Bull

- no foods with poppy seeds

- no nicotine-containing products, such as tobacco and nicotine plasters

- not donate blood or plasma until 3 months after the last visit

- as a male, use a barrier contraception (eg. condom) and not donate sperm until 4 months after the last visit

- females would need to have a negative pregnancy test, not be breastfeeding and must be unable to have children (eg. age reasons)

The poppy seed restriction meant missing my beloved seeded bread for 11 weeks or so. Other than that, my non-smoking, non-binge drinking habits and lack of caffeine had prepared me well for this trial’s “restrictions”.

Outpatient visits

My outpatients didn’t have a scheduled time but I was supposed to be there before noon, with a strong preference towards the time I was dosed, according to the doctors. My commute was an hour each way and so I had to wake up pretty early in the first week to get to my morning lectures on time. My total commute time has been 26 hours or so but I always took my laptop with me to do some work while on the train.

There are some more restrictions I had to follow before going in for an outpatient visit:

- no alcohol 72 hours before

- no caffeine or xanthine 24 hours before

During one of my outpatients, there was a man who decided to stop his trial. He mentioned having problems with urinating and had just generally had enough; I believe this was pretty early in his trial. In my last outpatient, there was a man doing a trial and afraid of needles!

The outpatient visit usually took less than 20 minutes:

- they ask how you’re feeling and if there are any health changes

- oral body temperature

- blood pressure

- blood samples

- occasional physical examination

- occasional urine sample

- occasional ECG

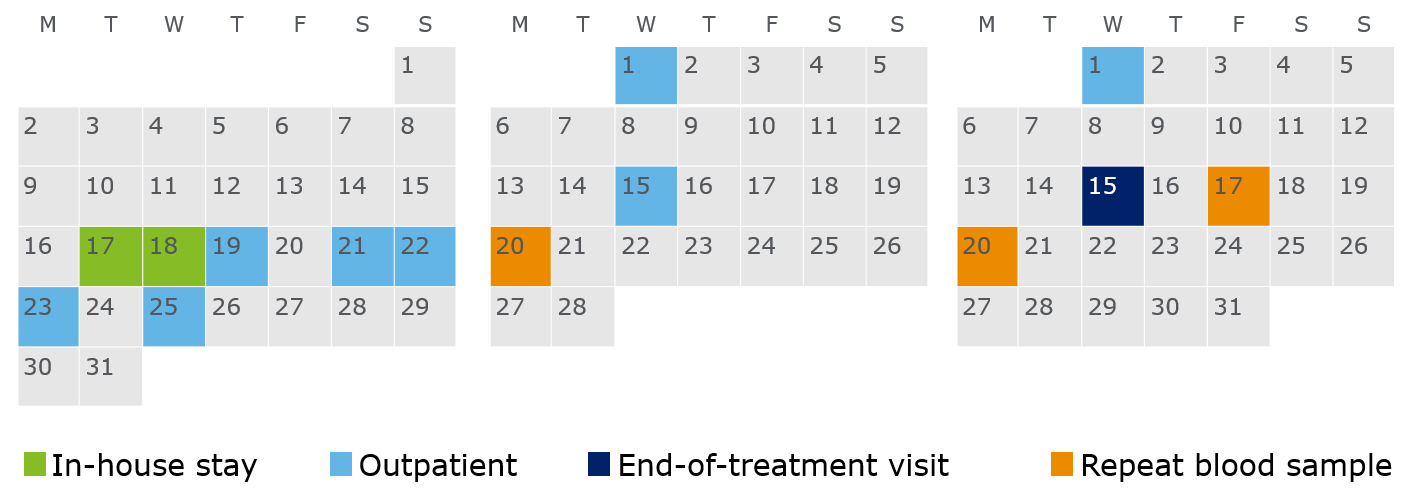

The calendar below shows my dates for the 1-night stay, 9 outpatients and 3 repeat blood samples. After an outpatient, you might be recalled for another blood sample, mostly because they want to check an abnormal value they measure in your blood is just an anomaly and not an effect of the study drug. Twice I needed to repeat because I had a low neutrophil count and once due to my potassium level being on the high side of normal. After the first repeat, you get compensated £20 per repeat; I had 3 repeats so I got an extra £60.

I didn’t realise at screening, but the dates I was given were perfect for me. Apart from the first 4 outpatients in the first week, the rest fall on Wednesdays, which I had free. So if you’re going to do a trial, dates and availability are very important to keep in mind. If your commute time is long I would highly suggest you go for fewer outpatients and more nights in-house.

Some people on my trial will get a placebo and no one will ever know if they are one of them, even after the study finishes. They say the fact is inside a sealed envelope that is only opened in medical emergencies to determine whether special measures should be taken. The outpatient nurses don’t know if someone has been given a placebo so they treat everyone the same. The nurses at Parexel were very friendly and caring.

What I discovered

…about myself

I’m objectively quite healthy, if not greatly so, although I wouldn’t go as far as claiming I have great fitness. I thought I drank quite enough water but I should be drinking even more, and I’m not just saying this because I had to drink a lot more because of blood samples.

I generally have a low (but still normal) count for neutrophil, the most abundant type of white blood cell. This is very likely to happen to (young, male) people of African descent, as backed up by this research article.

Research units

Below are some of the units I’ve come across that run clinical trials. I’ve heard Simbec and some other units might compensate for screening too. I’ve heard HMR has a very professional and timely administration.

- PAREXEL (London and some other global locations)

- Hammersmith Medicines Research (HMR)

- Simbec (South Wales)

- Imperial Clinical Research Facility (relatively low pay compared to the above from what I’ve seen)

2006 TGN1412 incident

While writing this article I came across the BBC Two documentary, The Drug Trial: Emergency at the Hospital. In 2006, Parexel—the same research unit I went to—started running a first-in-man study for TGN1412, a drug aiming to treat leukaemia (blood cancer). On the first cohort, the health of all 6 volunteers not given a placebo deteriorated and within the same day, they ended up in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of the host hospital. Since then, it has changed how medical trials are done.

The study drug was injected for the first time into humans after successful animal tests, human modelling and the government’s approval. The volunteers were agreeing to 3 nights and 12 outpatients before getting £2,000. The purpose of the study:

A first-in-man study to investigate the effects in healthy male volunteers of single doses of a new drug for the potential treatment of various inflammatory diseases.

Study Title:

A Phase-I, Single-Centre, Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Single Escalating-Dose Study to Assess The Safety, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics And Immunogenicity Of TGN1412 Administered Intravenously To Healthy Volunteers

The 6 men’s symptoms included hypothermia, loss of bowel control, migraines coming in waves and at least 4 of them with multiple organ failure. Once the Parexel study staff realised the deterioration’s extent, they moved them to the ICU of Northwick Park Hospital—in the same building—where it now became the job of the National Health Service (NHS) to save their lives.

The story caught on in the media at the time that they looked like the “Elephant Man” after a family member described what they saw. Dr Ganesh Suntharalingam (Consultant in Intensive Care Medicine and Anaesthesia at Northwick Park Hospital at the time and later Clinical Director of Critical Care there) in his personal view of the whole event, wrote:

In truth, it was not a specific symptom or effect of the drug, or some kind of explosive growth of the head. Critically ill people develop leaky blood vessels and shock, and the large volume of fluid we give them in the first few hours causes temporary swelling—most noticeable in the face. It gets better as they recover, but can look understandably upsetting to their friends and family.

After 2 days, they started feeling better simultaneously and almost miraculously. After 7 days, 4 out of 6 were out of ICU. After 21 days, one man was still in ICU. After 4 months, this man sadly had part of his fingers and toes amputated. Images are graphic. It is thought that because they had no bad cells (cancer), their good cells were eaten away.

What came in the investigations after included praise to the NHS and Northwick Park Hospital. The fact that the trial was done in a major hospital with an ICU, gave them a much better chance of survival. The study was criticised for administering the study drug 10 times quicker into the bloodstream of the 6 humans than into monkeys during earlier animal trials, even though the men effectively got a much smaller volume.

An independent report made 22 recommendations to improve the safety of first-in-man studies internationally. Some of these have been implemented in the whole of Europe. Clinical trials are now safer than at any other time before.

The first man to be injected is now married with 3 kids. He is glad to have been saved by another drug and still values the importance of clinical trials.

Conclusion

Knowing what I know now, would I go back and do it again?

Yes.

Would I do a second clinical trial?

Yes, depending on time requirements and my availability.

I got paid £1,760 for a total of 31 hours in the unit (including lounge room time and 8 hours of sleep) and 26 hours of commuting. That’s an insane hourly wage for a student. There is of course always some risk and it depends on the trial but to be fair, you perhaps have more risk by simply living in a big city (air pollution, violent crime) than by doing most trials. In the UK at least, how much you are paid depends on the time commitment and the medical assessments’ intrusion and not by the health risk involved.

If anything, what has surprised you the most from this article? Comment below. If you’ve done a clinical trial before, comment on your experiences, especially if at a different research unit.